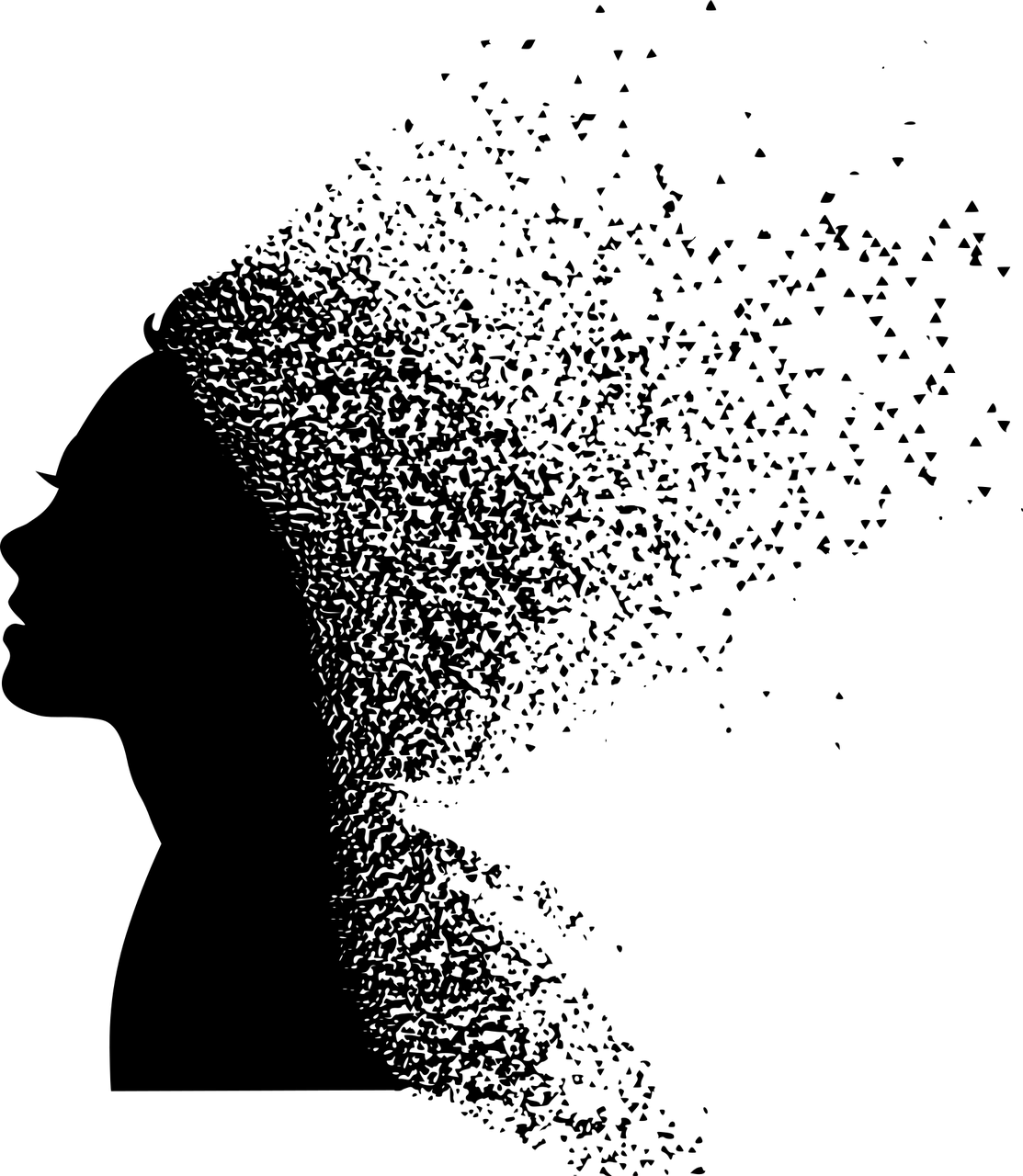

As many of us know, surviving trauma can cause the brain to remain in a state of protracted hypervigilance and intense emotional reactivity. It can also subject the brain to a state that many of us may be familiar with: dissociation (also referred to as disassociation).

In their groundbreaking book, The Stranger in the Mirror: Dissociation—The Hidden Epidemic, Dr. Marlene Steinberg and Maxine Schnall define dissociation as “an adaptive defense in response to high stress or trauma characterized by memory loss and a sense of disconnection from oneself or one’s surroundings.”

In the wake of trauma, almost 75% of people will find themselves in a dissociative state—either shortly after the traumatic event or for hours, weeks, months, even years to come. Many times, dissociation will end on its own, but in some cases, it can become a recurrent aspect of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Dissociation, based on Steinberg and Schnall’s observations, encompasses five major symptoms:

- Amnesia: Memory loss that may be general or hyper-specific, often focused on one incident or period of time associated with the traumatic event

- Depersonalization: Disconnection from the body and emotions, almost like you’re on autopilot, just going through the motions

- Derealization: The sense that the world around you isn’t real, which includes disconnection from people, places, and situations that once felt familiar

- Identity confusion: A sense of uncertainty around who you are

- Identity alteration: Marked changes in your personality that you may not feel you have control over (this form of dissociation is common in multiple personality disorders)

To some extent, people can experience dissociation even when they aren’t under duress. This might include experiences like being on autopilot when you drive to work, and not knowing exactly how you got there because you were preoccupied with something else; uncertainty about what exactly you’re feeling; detaching from the bodily sensation of needing to use the restroom when you’re in the midst of an important meeting; or even just merely daydreaming. The “flight” factor in the nervous system’s fight-or-flight response contributes to dissociation, and it’s specifically meant to reduce the experience of being overwhelmed by a distressing situation. However, dissociation can be disruptive when it’s the result of trauma. Although it can shield people from the painful memories and emotions that are part of that trauma, dissociation becomes pathological when the brain completely separates from its awareness of the self. There is a lack of control over the body and mind that can be bewildering to the person experiencing it. Dr. Karl Deisseroth, a professor of psychiatry at Stanford University, describes dissociation “as the perception of being on the outside looking in at the cockpit of the plane that’s your body or mind—and what you’re seeing you just don’t consider to be yourself.”

Deisseroth and his colleagues at Stanford University determined that when dissociation occurs, neurons fire together at a specific rhythm in the posteromedial cortex, the part of the brain that controls self-awareness, self-processing and consciousness. They found that a specific protein is responsible for the 3 Hz rhythm that’s connected to the experience of dissociation. Scientists believe that the identification of this protein can help them to actively treat dissociation, which is especially significant in light of the fact that dissociative disorders are risk factors for suicide and other forms of self-harm.

Working with a therapist and learning grounding techniques for dealing with dissociation can go a long way in helping to treat it. Many of these methods encourage an intentional engagement with the senses, which enables us to ground down, back into our bodies. These grounding methods can strengthen the hippocampus, which aids in a stronger memory function. They can also strengthen the prefrontal cortex, which contributes to our sense of logic and control. Moreover, they mute the influence of the amygdala—an effect that helps us to feel safe and at peace.

Soul work is connected to changing the way our brain works. Remember, although moving through trauma can be painful, you aren’t alone—and the neuroplasticity of the brain means we are capable of change and growth, no matter what stage of our life we may be in.